|

||

|

|

||

| Wednesday, May 5, 2004 |

|

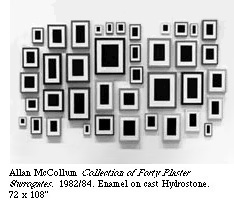

MOMA AT MAM Re-presenting the modern by any means By KATE THOMSON Special to The Japan Times "So what's modern art all about?" is a question I am often asked. It's about as easy to answer as "What is the meaning of life?"

It's interesting, then, that the Mori Art Museum extends the term up to the present with its new exhibition, "Modern Means: Continuity and Change in Art, 1880 to the Present," which opened April 28. It's an incisive look at what modern art is, and an examination of its continuing relevance. The works on show are drawn from the definitive collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Alfred H. Barr Jr., who became the first director of MoMA in 1929, pioneered a new kind of museum. He shared the dream of the founders of Bauhaus, the German architecture and design school that embraced all the visual arts. Barr promoted what he believed was the best art of his time, including film, photography, architecture and design as well as the traditional media of painting, sculpture and works on paper. Both David Elliott, director of MAM, which opened last year, and Glenn D. Lowry, the director of MoMA -- whose current reconstruction is the reason so many works are available for loan here -- are concerned with the need for art museums to adapt to changes in contemporary society and nurture new artists. As Lowry said at a press conference last week, "MoMA stands for the history of modern art, but must also stand for a constant reassessment of that tradition in constant flux." Curators Deborah Wye and Wendy Weitman chose four themes -- Primal, Reductive, Common Place and Mutable -- through which to explore more than 250 works. They use the benefit of hindsight to cross-reference different mediums and time periods, and to articulate relationships between disparate art movements. The result successfully places artists in the context of their own time and ours; and in doing so also speculates on future directions for artists and museums. Primal shows how artists use abstraction to focus on gestural expression, exploring their hunger to understand elemental forces in life (sexuality, death, illness, desire and anxiety) and the unconscious mind with works from Pollock to Keiffer. Obvious inclusions are some of Gauguin's Tahitian works, embodying his search for social freedom; more unexpected expressions of the human sprit in tune with nature are seen in the examples of Art Deco furniture by architect and designer Hector Guimard. Auguste Rodin's "The Three Shades" is a passionate and timeless expression of human drama. Rodin was the father of abstract sculpture -- his emphasis on paring things down to their essence was one of the few shared practices of the Modernists, and is now firmly established in the artistic canon. In Reductive we see the process developed, with artists and designers stripping away inessential detail to reveal the "purity" within the form. Their abstract visual language has become the basic grammar still used in interpreting the world around us. Architect and designer Gerritt Rietveld and painter Piet Mondrian of the Dutch de Stijl group epitomize the evolution of pure-color and geometric abstract expression. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's dictum of "less is more" -- captured here in his "MR Side Chair" (1927) -- was central to the quest of movements such as Bauhaus, de Stijl, Russian Constructivism and International Style for a clarity of vision able to represent universal truths and cosmic harmonies in an age shocked by the horrors of war. Sol Lewitt has been called the "inventor" of Conceptual art. In his "Cubic Construction" (1971) he employs the Minimalist ideal of purity devoid of gesture to engage the mind rather than the emotions. Although he claimed to deny craft, the beauty of proportion and form shines through because of the craftsmanship. Playing with both Minimalism and concepts of mass-production, Allan McCollum's "40 Plaster Surrogates" (1982-84) challenges the idea of "rarity" in art by creating unlimited multiples of monochrome panels. This comment on value leads well into the explosion of commercial imagery in Common Place, which considers how art has responded to and absorbed mass media and popular culture. The beauty that modern artists found in the ordinary, and their transformation of the familiar to comment on or criticize society shocked the public and critics alike. But ironically, works like Robert Indiana's "LOVE" (designed as a MoMA Christmas card), and Andy Warhol's "Marilyn Monroe," both painted in 1967, became mass-media icons in their own right. Parallel themes of transformation and metamorphosis are taken to a more metaphysical conclusion in Mutable, where the unnerving impermanence of the modern world is expressed in anticlassical media -- most of the exhibition's video work is contained in this section. These works are surprisingly accessible, using wit and acute observation to seduce viewers into contemplating their place in society and the environment. From Rene Magritte's "The Empire of Light" (1950) to Robert Gober's disembodied pair of legs stuck with candles ("Untitled," 1991), the artists challenge perceptions of reality. The fascination of art is that it engages both our primal instincts and our intellect to search for answers to eternal questions. If we stop asking questions, we are culturally dead. This exhibition is proof that modern art is very much alive, and there is continuity supporting change. Tradition and innovation together push beyond existing boundaries of experience. Asian artists seem under-represented here, but this is a collection formed at a time of American and European experimentation. As Elliott remarked at the opening, "In a world no longer so dominated by Western values, there is little doubt that exhibitions like 'Modern Means' will in the future contain many more non-Western works -- indeed they will have to, if they are to reflect the ways in which our world and its art continue to change." I look forward to seeing how both MoMA and MAM promote current and future developments. In the meantime, though, this exhibition is a provocative and illuminating exposition of how we got to where we are now. "Modern Means" runs till Aug. 1 at the Mori Art Museum, Roppongi Hills 53F; admission 1,500 yen. For more information, see www.mori.art.museum Kate Thomson's work can be seen at www.ukishima.net and in a joint exhibition with Hironori Katagiri, May 14-29, at Space TRY Gallery, 4-19-20 Shirokanedai, Tokyo; (03) 3447 2559 The Japan Times: May 5, 2004 |

|

About us / Contact us / Advertising / Subscribe News / Business / Opinion / Arts & Culture / Life in Japan Sports / Festivals / Cartoons Advertise in japantimes.co.jp. This site is optimized for viewing with Netscape or Internet Explorer, version 4.0 or above. The Japan Times Ltd. All rights reserved.

|