|

|

|

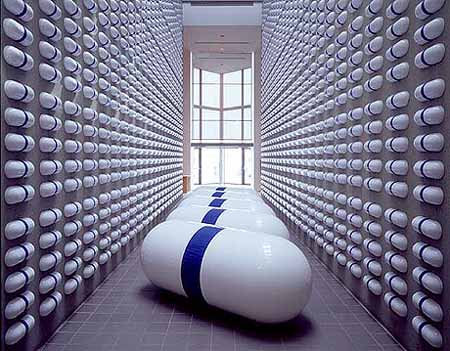

On floor: One Day of AZT. 1991. Five fiberglass units, each 33 7/16 x 84 1/8 x 33 7/16" (85 x 213.7 x 85 cm). Collection General Idea, Toronto On walls: One Year of AZT. 1991. 1,825 units of vacuum-formed styrene with vinyl, each 4 7/8 x 12 3/8 x 3" (12.4 x 31.5 x 7.4 cm). Collection National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa |

|

General Idea LILIAN TONE We knew in fact what we wanted to share with you. We wanted to point out the wildly fluctuating interpretations you, our public, impose on us. Under your gaze we become everything from frivolous night-lifers to hard-core post-Marxist theoreticians. We wanted to point out the function of ambiguity in our work, the way in which ambiguity "flips the meanings in and out of focus," thus preventing the successful deciphering of the text (both visual and written) except on multiple levels. Curiously many of you choose only to read one side to any story. Since we give a wide range of choices (and we are conscious of the politics of choice) we are never sure which side you, our readers, will take.... – General Idea 1bitter pills If proper names are particular and the rest of the language is general, then the choice of General Idea as a proper name proclaims, from the start, the ambiguous identity of this Canadian artists' collective. In addition to its military and corporate undertones, the name's fundamental contradiction—a particularity defined by a generality—must have appealed to founders Jorge Zontal, Felix Partz, and AA Bronson. During twenty-six years of professional and domestic partnership—one of the longest collaborations in twentieth-century art—which ended in 1994, the members of General Idea consistently wove this kind of elusive meaning and literate wit into their resonant body of work. Wielding sharp but whimsical wordsmithery, visual acuity, and a command of various mediums, they focused on cultural emblems, continuously alternating between undermining and exalting their chosen object. General Idea began operations in Toronto around 1968, a time when the stereotype of the artist as individual genius was forcefully being put into question. As part of an effort to recruit new audiences, the group quickly adopted a strategy of appropriating unconventional artistic formats from the mass media and popular culture: beauty pageants, television shows, popular magazines. Inserting novel content into familiar forms, General Idea managed to slip their unsettling messages past the audience's guard, while always replacing received truths with something less certain. Although Conceptual artists resorted to similar strategies, General Idea's approach has always lacked the often didactic and theoretical inflection of much of that movement. Instead, their work is marked by humor and ambiguity, qualities largely unassociated with Conceptual art. Its pervasive tone of sexual ambivalence and its open play with gay stereotypes would become a liberating influence for a number of artists in the 1980s; also important for this later generation was its direct treatment of issues relating to the artwork as commodity. Following the lead of Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol, and Yves Klein, the members of General Idea sought to operate in what they defined as the "gap between culture and nature." Each individual work suggests itself as a residue, an index of some vast, unattainable project. In the presence of such works, one is often struck by the suggestion of what remains unseen, by the missing threads of the story. Like many Conceptual artists, the group made writing and publishing a major vehicle of their work and, in April 1972, began issuing a periodical, FILE Megazine. The typography of FILE mimicked that of LIFE magazine, and it became the main outlet for the group's interest in language, as well as a powerful means of networking for artists. The editorials of FILE show a keen sense of the absurd and the outrageous, with a special fondness for double entendres and tasteless puns. Between FILE and Art Metropole, the archive and artists' space the three founded in 1974, General Idea created and nourished an international audience with performances, videos, publications, exhibitions, and shops, establishing a homegrown system of communication and distribution.

In Roland Barthes's writings, General Idea found a ready-made collection of ideas on which to draw—notions like the death of the author, and, more specifically, Barthes's brilliant examination of the construction of myth. During the eighteen years preceding the AlDS-related projects General Idea began in 1987— among them the installations that are the subject of this exhibition—they painstakingly built a complex mythological edifice that allowed them to internalize as well as to comment upon the art world. This edifice had "five elements . . . : 'General Idea' as representing the 'artist'; 'The Miss General Idea Pageant,' which we think of as the process of creation; 'Miss General Idea' as the artwork itself; 'The Miss General Idea Pavilion,' which is clearly the museum or the gallery; and what we call 'Frame of Reference,' which is essentially the audience and the mass media." 2 During a time of heightened feminist awareness, General Idea incongruously created performances in the form of beauty pageants from 1968 through 1978. In the same deliberately contrarian vein, they used poodle images amidst a climate of increasing liberation from effete gay stereotypes. Common to their signature motifs—ziggurats, cornucopias, poodles—was "the possibility of considerable proliferation, a lot of potential meanings, and graphic potential."3 Through the late 1970s, they conceived projects for the "1984 Miss General Idea Pavilion," a succession of multisite stagings incorporating their iconography and intended to house their final performance, the 1984 Miss General Idea Pageant, during George Orwell's fateful year. Ultimately, however, General Idea destroyed its metaphorical pavilion by setting an equally metaphorical fire. Much of their subsequent work dealt with the fire's cathartic aftermath, turning them from architects of the imaginary into its archaeologists. After 1987, General Idea largely stepped out of the Miss General Idea structure, focusing instead on projects dealing with AIDS and its implications. Their formal vocabulary and art-making strategies, however, remained as varied as ever. In response to an invitation to participate in a major "Art Against AIDS" benefit organized by AMFAR (the American Foundation for AIDS Research) in 1987, General Idea resuscitated a previously discarded project based on Robert Indiana's famous "LOVE" logo, for which they remade the classic good-vibrations symbol to read "AIDS." The painting compressed the letters A-l-D-S into two rows within a perfect square, in close hues of green, red, and blue–functioning exactly like Indiana's original painting of 1966. They thus created "an aura of familiarity that would allow a more alarming content." 4 By "inhabiting" (to use a term the group took from Barthes) a 1960s icon, they forged one for the 1980s. As with their previous work, the AIDS logo is open to multiple interpretations, frustrating demands for explicit militancy and risking criticism for treating such a serious issue with apparent frivolity. 5 Propriety and political correctness had never been General Idea's forte.

One should note that before 1987, relatively few artworks dealt specifically with AIDS. At that time, AIDS was a charged word, more frequently whispered than spoken. As American AIDS activist groups stressed, President Ronald Reagan had yet to say the word AIDS in public by that year. The social stigma attached to the disease made its adoption as subject matter uneasy amid the economic optimism of the 1980s. It is this context of denial and prejudice that General Idea was addressing and attempting to destabilize: "We want to make the word AIDS normal. AIDS is sort of playing the part that cancer did in the sixties. By keeping the word visible, it has a normalizing effect that will hopefully play a part in normalizing people's relationship to the disease–to make it something that can be dealt with as a disease rather than a set of moral or ethical issues." 6 What attracted General Idea to Indiana's LOVE was not only that image's emblematic power and openness to multiple meanings, but also how it made its way into popular culture. Indiana produced several artworks based on it: variations of the painting in different colors, formats, and configurations; a small aluminum sculpture multiple; a monumental-sculpture in steel; an eight-cent stamp; and various editions of prints. LOVE had such universal appeal that versions of it popped up in the most unexpected applications, from cocktail napkins to key chains. Following LOVE's example, General Idea produced several versions of AIDS: a small metal sculpture, a monumental metal outdoor version (which is allowed to accumulate often homophobic graffiti each time it is exhibited), a postage stamp, numerous paintings exploring all combinations of split complementaries plus white-on-white and black-on-black, and also two versions in screenprinted wallpaper. But more important, and ultimately responsible for the image's ubiquity, were the countless temporary AIDS projects realized outside the museum and gallery context, involving posters pasted on the streets and public transport vehicles, as well as lottery tickets and magazine covers. The idea was to infiltrate the image into as many contexts as possible—akin to the dissemination of an "imagevirus" in communication and distribution systems, simulating the spread of the HIV 7 —while actively seeking to lose control of its usage and deliver it fully into the visual vernacular. In 1991, General Idea developed three installations containing cast-fiberglass "megapills." Adhering to the original AIDS logo's red-green-blue color scheme, these installations are nearly identical, the only difference being that one color is dominant in each, hence their titles: Red (Cadmium) PLA©EBO, Green (Permanent) PLA©EBO, and Blue (Cobalt) PLAC©EBO. On the floor lie three monumental, human-size pills, each featuring the dominant color (in combination with itself or one of the other two). A series of accompanying wall reliefs consists of foot-long pills arranged in groups of three along the wall, exhausting all twenty-seven possible permutations of the color groupings on the floor. 8

Placebos are pseudo-medications that in fact do not contain an active ingredient—"candy-coated sugar pills [that] fake your body into feeling better while leaving it defenseless."9 When used for experiments testing drugs for terminally ill patients, placebos raise ethical dilemmas by endangering individual lives for the ultimate good of the many. As General Idea tells us, the etymology of the term placebo goes back to the Latin placere, meaning "to please." In General Idea's vocabulary, placebos serve as surrogates for art, functionless and soothing. Consistent with this notion is the deceptively cheerful appearance of the PLA©EBOs: Saturated color radiates from the liquid gloss of the pills' surfaces, investing these stand-ins for both treatment and disease with an impertinent lightheartedness. A strange disorientation results from their gigantic proportions. The application of such dimensional shifts to everyday objects had already proven a powerful expressive tool for Pop artists, invariably promoting a sense of displacement. The PLA©EBO installations draw their unsettling effect from the impact of this device on our ingrained perceptual habits. Immediately following the PLAC©EBOs, another highly charged subject motivated two of General Idea's most spectacular installations, both featured in this exhibition. AZT (Azydothymidine), produced by the Burroughs Wellcome Company and licensed by the Food and Drug Administration in 1987, was the first antiviral compound to become available to AIDS patients. While not a cure, AZT had proven fairly successful in helping to retard the replication of the virus, despite high toxicity and awful side effects.10 Controversy surrounding its lengthy approval process was compounded by the issue of availability to patients: Its astronomical price tag put it beyond the reach of many who wanted to pursue treatment. One Day of AZT (1991) displays the daily dose of the drug—then five capsules—as human-size pills on the floor. In addition, 365 sets of five smaller pills, in bas-relief—one for each day of the year—are arranged in monthly sequences along the walls, adding up to One Year of AZT (l991). Inducing a state of disembodied suspension, the numbing regularity and relentless repetition of the daily dose sets up a sad visual mantra that evocatively counts down the passing months. An undercurrent of tension derives from the friction between formal elegance, with its aestheticizing denial of the pills' function, and a pervasive aura of foreboding. Bearing in mind General Idea's preference for found form, art-historical references sharpen into focus in a museum context. Within a clinical, antiseptic gallery space, the serial geometric arrangement becomes reminiscent of Minimal art, while the appearance of the medication—a contrasting cobalt blue stripe over the white expanse—alludes to hard-edge abstractions. As opposed to the PLA©EBO pills, fabricated in fiberglass, the AZT wall pills are vacuum-formed in styrene with vinyl, better approximating in appearance the real AZT casing. Like all their pharmaceutical counterparts, General Idea's AZT pills are aerodynamically designed for smooth and unimpeded descent, aesthetically perfect objects whose associations constantly intrude on one's admiration. Thus displaced and decontextualized, the pills' fruitless mission is relegated to a phantom place in the viewer's mind, misleadingly suggesting, as with so much of General Idea's work, that they aim at nothing other than an illicit pure beauty. With Jorge Zontal's death of AIDS-related causes in 1994, General Idea was prematurely dissolved at a creative peak. Four months later, Felix Partz also died as a result of AIDS. This exhibition is dedicated to their memory. Lilian Tone I am grateful to the many colleagues who shared their expertise and provided helpful suggestions. A special thank you to Sherrie Levine, for planting the seeds for this exhibition; Oswaldo Costa, for his unflagging enthusiasm and loving support; and AA Bronson, for kindly and patiently guiding me through General Idea's remarkable work | ||||||||||

|

Notes: 1. General Idea, "Editorial: You–You're the One," FILE Megazine (Summer 1978), p. 7.2. 2. AA Bronson, cited in Joshua Decter, "General Idea," Journal of Contemporary Art (Spring Summer 1991), p. 54. 3. 3. Felix Partz, cited in Decter, "General Idea," p. 56. 4. 4. General Idea, quoted in Sandra Simpson, "Questions to General Idea," in General Idea: Multiples (Toronto: S. L Simpson Gallery, 1993), n. p. 5. 5. See Allan Schwartzman, General Idea The AIDS Project (Toronto: The Gershon Iskowitz Foundation, 1989), p. 5. 6. AA Bronson, cited in Decter, "General Idea," p. 58. 7. General Idea's notion of image as virus comes from William Burroughs and originally appeared in FILE Megazine in 1973. See "Pablum for Pablum Eaters," FILE Megazine vol. 2, nos 1 2 (April-May 1973), p. 26. 8. See General Idea in Simpson, "Questions to General Idea," n. p. 9. General Idea, "General Idea's Pharma©opia," in General Idea: Pharma©opia (Barcelona: Centre d'Art Santa Monica, 1992), p. 61. 10. Today, in combination with protease inhibitors and other new drugs, AZT has become markedly more effective as an agent for extending the life of people with AIDS. _______ biography aa bronson felix partz jorge zontal _______ This essay accompanied "Bitter Pills," a projects exhibition curated by Lilian Tone at the Museum of Modern Art, November 28, 1995 - January 7, 1997. The projects series is made possible by the Contemporary Exhibition Fund of The Museum of Modern Art, established with gifts from Lily Auchincloss, Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro, and Mr. and Mrs. Ronald S. Lauder; and grants from The Contemporary Arts Council and The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art, and Susan G. Jacoby. Editor: Rachel Posner. ©1996 The Museum of Modern Art, New York | ||||||||||