The issue of scale, from the minuscule to the massive, has been a prime concern of many artists in past decades. As an indicator of our relation to the "real," scale becomes all the more relevant as technology assumes greater importance in our daily lives. Increasingly, our access to works of art takes place largely through reproductions — a world of books, posters, postcards, and electronic media — radically transforming the experience of art. In contrast, the works gathered in this exhibition promote and reiterate direct experience.

The issue of scale, from the minuscule to the massive, has been a prime concern of many artists in past decades. As an indicator of our relation to the "real," scale becomes all the more relevant as technology assumes greater importance in our daily lives. Increasingly, our access to works of art takes place largely through reproductions — a world of books, posters, postcards, and electronic media — radically transforming the experience of art. In contrast, the works gathered in this exhibition promote and reiterate direct experience.

The growing prevalence of this disembodied artistic experience may have contributed, in reaction, to an increased interest in the ways in which only the actual object can affect the viewer. Contemporary artists have manipulated scale and explored magnification and miniaturization — languages widely employed in digital technologies — as a means of expression. In direct confrontation with the viewer's body, the physically present object proposes unexpected relationships, inducing a heightened state of spatial awareness, a sense of uneasy familiarity, or other potentially uncanny states of mind.

The growing prevalence of this disembodied artistic experience may have contributed, in reaction, to an increased interest in the ways in which only the actual object can affect the viewer. Contemporary artists have manipulated scale and explored magnification and miniaturization — languages widely employed in digital technologies — as a means of expression. In direct confrontation with the viewer's body, the physically present object proposes unexpected relationships, inducing a heightened state of spatial awareness, a sense of uneasy familiarity, or other potentially uncanny states of mind.

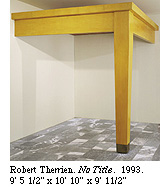

Several works of contemporary art in The Museum of Modern Art's collection speak to issues of scale in distinct ways, from those who expand or diminish expected dimensions to those which represent things on a one-to-one scale. Robert Therrien's No Title (1993) consists of an oversized wood table appearing to emerge from the corner of a room, with a single leg protruding from the wall. No Title 's gigantism belies its generic appearance. Over nine feet high, it has a quasi-architectural impact: the viewer can walk under it, look up at it, be sheltered by it. While evoking a child's vantage point, No Title, in fact, derives from Therrien's use of photography to register usual objects from unusual, fragmented points of view, unhinging our customary surroundings and de-stabilizing the familiar world.

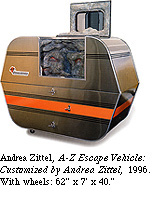

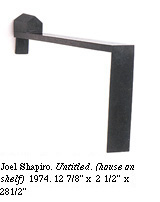

At the other extreme of scale disruption, Joel Shapiro's Untitled (house on shelf) (1974) plays with the viewer's perception by rendering a schematic house in diminutive size, as if seen from a distance. Installed at eye level, perspectival illusion is reinforced as the eye follows the protruding shelf on which the house sits, as if at the end of a lane. Subliminally, the piece also references the lilliputian world of toys, but this ponderous little structure has a gravity beyond that achievable by any counterpart made from wooden blocks. The suggestion of childhood, but from the perspective of the imaginary, also appears in Andrea Zittel's A-Z Escape Vehicle: Customized by Andrea Zittel (1996), one of a series of four customized trailer-like vehicles. Behind their high-modern sleekness lie miniaturized, fantasy spaces conceived for a single individual. Tailored by the artist for herself, it functions as a shrunken habitat, inspired by memories of a visit to a grotto constructed by Ludwig II of Bavaria.

At the other extreme of scale disruption, Joel Shapiro's Untitled (house on shelf) (1974) plays with the viewer's perception by rendering a schematic house in diminutive size, as if seen from a distance. Installed at eye level, perspectival illusion is reinforced as the eye follows the protruding shelf on which the house sits, as if at the end of a lane. Subliminally, the piece also references the lilliputian world of toys, but this ponderous little structure has a gravity beyond that achievable by any counterpart made from wooden blocks. The suggestion of childhood, but from the perspective of the imaginary, also appears in Andrea Zittel's A-Z Escape Vehicle: Customized by Andrea Zittel (1996), one of a series of four customized trailer-like vehicles. Behind their high-modern sleekness lie miniaturized, fantasy spaces conceived for a single individual. Tailored by the artist for herself, it functions as a shrunken habitat, inspired by memories of a visit to a grotto constructed by Ludwig II of Bavaria.

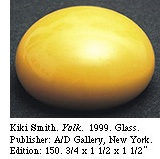

Certain contemporary artists have addressed the issue of scale in exacting, literal ways, creating works in a one-to-one relation with the object being represented. With varying degrees of similitude, these works pose as slightly twisted duplicates of the real. Often painstakingly manufactured, they undermine absolute notions of true and false, bridging the distance between the authentic and the artificial. From Andy Warhol's Brillo Box (Soap Pads), 1964, to Kiki Smith's Yolk, 1999, these are works whose identities and allegiances shift from props to doubles, stand-ins to facsimiles, and whose insistent theatricality often tricks the viewer's perception. Although these works obviously share a keen affinity with Marcel Duchamp's readymades, they are not unmanipulated found objects, though they may look that way. Like readymades, these works raise questions about where life ends and art begins, yet their handcrafted character and use of artistic materials seem to imply a desire to feed the paradox of appropriating something from the world while engaging the language of art. Ironically, they are fabricated readymades.

Certain contemporary artists have addressed the issue of scale in exacting, literal ways, creating works in a one-to-one relation with the object being represented. With varying degrees of similitude, these works pose as slightly twisted duplicates of the real. Often painstakingly manufactured, they undermine absolute notions of true and false, bridging the distance between the authentic and the artificial. From Andy Warhol's Brillo Box (Soap Pads), 1964, to Kiki Smith's Yolk, 1999, these are works whose identities and allegiances shift from props to doubles, stand-ins to facsimiles, and whose insistent theatricality often tricks the viewer's perception. Although these works obviously share a keen affinity with Marcel Duchamp's readymades, they are not unmanipulated found objects, though they may look that way. Like readymades, these works raise questions about where life ends and art begins, yet their handcrafted character and use of artistic materials seem to imply a desire to feed the paradox of appropriating something from the world while engaging the language of art. Ironically, they are fabricated readymades.

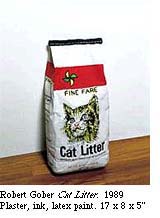

Robert Gober's humorous yet often macabre incursions into the homely have included sinks, beds, plywood sheets, bundles of newspaper, bags of kitty litter, and body parts rendered in actual size. In Cat Litter, 1989, the artist celebrates the informal domesticity of daily life by personally remaking a prosaic reminder of its everyday chores. The work may pass for the real thing from a distance, though nothing is done to disguise the unmistakable signs of the human hand. The lettering and other graphic elements are all quirkily hand-painted on plaster, counteracting any expectation of slick, industrial packaging. Adding a certain ambiguity to its already uncertain artistic status, Cat Litter sits directly on the floor, leaning against the wall nonchalantly, much as a bag of litter might in someone's home.

Robert Gober's humorous yet often macabre incursions into the homely have included sinks, beds, plywood sheets, bundles of newspaper, bags of kitty litter, and body parts rendered in actual size. In Cat Litter, 1989, the artist celebrates the informal domesticity of daily life by personally remaking a prosaic reminder of its everyday chores. The work may pass for the real thing from a distance, though nothing is done to disguise the unmistakable signs of the human hand. The lettering and other graphic elements are all quirkily hand-painted on plaster, counteracting any expectation of slick, industrial packaging. Adding a certain ambiguity to its already uncertain artistic status, Cat Litter sits directly on the floor, leaning against the wall nonchalantly, much as a bag of litter might in someone's home.

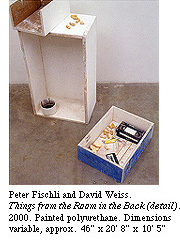

Addressing more directly the tradition of trompe l'oeil (fool the eye), Things from the Room in the Back by the Swiss artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss, shares with Cat Litter the ability to disconcert viewers while challenging preconceived definitions of art. In Things from the Room in the Back, what appears to be the leftovers of an installation in progress, or the circumstantial evidence of work at an artists' studio, on closer inspection reveals itself to be a group of painstakingly made replicas of pedestals, pieces of lumber, buckets of paint, orange peel, peanut shells, an X-Acto knife, a felt-tip pen, a videotape, a cassette tape, a Kodak film package, and other prosaic objects. These objects, most of which are found around the studio, are carved in polyurethane and then painted to achieve a high degree of illusionism. While there is a long tradition of artists who have deliberately made artworks that do not look like art, few have done it so well as to make the work of art nearly disappear. Fischli/Weiss have a talent to detect the precise point where familiarity makes us stop looking. This is especially ironic given the fact that Things from the Room in the Back is a work that requires hard looking to be perceived as art.

Addressing more directly the tradition of trompe l'oeil (fool the eye), Things from the Room in the Back by the Swiss artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss, shares with Cat Litter the ability to disconcert viewers while challenging preconceived definitions of art. In Things from the Room in the Back, what appears to be the leftovers of an installation in progress, or the circumstantial evidence of work at an artists' studio, on closer inspection reveals itself to be a group of painstakingly made replicas of pedestals, pieces of lumber, buckets of paint, orange peel, peanut shells, an X-Acto knife, a felt-tip pen, a videotape, a cassette tape, a Kodak film package, and other prosaic objects. These objects, most of which are found around the studio, are carved in polyurethane and then painted to achieve a high degree of illusionism. While there is a long tradition of artists who have deliberately made artworks that do not look like art, few have done it so well as to make the work of art nearly disappear. Fischli/Weiss have a talent to detect the precise point where familiarity makes us stop looking. This is especially ironic given the fact that Things from the Room in the Back is a work that requires hard looking to be perceived as art.

The works in this exhibition inhabit the territory of the uncanny, triggering changes in our perceptions of reality, or even what constitutes the real, and disrupting our ideas of normalcy.

Lilian Tone

Assistant Curator

Department of Painting and Sculpture

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Grateful acknowledgement is due to Lianor da Cunha and Michelle Yun in the Department of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Strangely Familiar: Approaches to Scale in the Collection of The Museum of Modern Art

Artists exhibited: Richard Artschwager, William Bailey, Chuck Close, Edward Ruscha, Peter Fischli and David Weiss, Robert Gober, Katherina Fritsch, Neil Jenney, Toba Khedoori, Martin Kippenberger, Jeff Koons, Allan McCollum, Joel Shapiro, Laurie Simmons, Kiki Smith, Robert Therrian, Andy Warhol, Robert Watts, Steve Wolfe, Andrea Zittel.

Opens: April 5, 2003

Where: State Museum, Empire State Plaza at Madison Avenue, Albany

Hours: 9:30 a.m.-5 p.m. daily

Closes: June 29, 2003

Information: (518) 474-5877